REGRETS? HE’S HAD a few. At 68, Eamon Dunphy has finally completed the first volume of his highly anticipated autobiography, My Rocky Road, in which the former Irish international and veteran journalist seeks, as he recently explained, to “make people go: ‘okay, I get it’”.

Dunphy has long been one of the most divisive figures in Irish public life. To friends and admirers, he is a fearless rebel, a one-man BS detector whose honesty is both his biggest strength and weakness. Yet to his enemies, he is the very opposite — a charlatan. A bitter, brash, attention-seeker, who goes out of his way to attract controversy.

And perhaps somewhat surprisingly, Dunphy falls somewhere in between these two camps when assessing his life. “The idea of this book isn’t to show I’m a great person. In fact, it’s mostly to show I’m not great at all,” he tells TheScore.ie.

Such modesty is arguably surprising for someone whose caricature would be that of an altogether more narcissistic individual, but then even during his most supposedly obvious attention-seeking moment, the aftermath of Ireland’s disappointing 0-0 draw with Eygpt at Italia 90 in the RTE studio (see below), there was more than a hint of altruism amid this infamous spectacle.

“I’m thinking of all the great players we produced, the Peter Farrells, the Liam Bradys, the Ronnie Whelans, the David O’Learys,” he told Bill O’Herlihy and the millions watching at the time.

Even this week, Dunphy was quick to clarify what had happened in those heady days, pointing out that he never threw his pen, as has been alleged. He simply placed it on his desk and loudly sighed.

Yet the legend was printed instead of the truth. Word had gotten out falsely claiming that Dunphy declared himself “ashamed to be Irish”. Then-manager Jack Charlton led the chorus of disapproval. Having experienced his fair share of heated arguments over the course of an otherwise unremarkable career as a professional footballer, Dunphy was well accustomed to causing controversy, yet what followed was a storm unlike any he had ever experienced before.

“A lot of the players — pals of mine, Ronnie [Whelan], Ray [Houghton] — they knew what I was writing was right. But at that stage, everyone from Mary Harney to Nell McCafferty was an expert on football. So I ended up taking a phone call from Mary Harney telling me to ‘stop making a fool of myself’. F**king Mary Harney, I’d been playing football since I was three and she didn’t know her way to Dalymount Park. There was madness in the air.

“People had a great time — that’s the point. When we beat England in 88, watching the World Cup in 1990, people didn’t care about the football, but they knew something fantastic was happening. It was better than the Eurovision song contest and it went on longer. Ireland was in party mood for a few years and soccer was at the epicentre of that and here was this arsehole going around in the middle of it saying ‘soccer’s no good’, ‘why aren’t you joining in?’ Soccer wasn’t our game anymore. They stole it. But I’m not saying they weren’t entitled to it, they were.”

YouTube credit: Mare Footage

Charlton, by that stage a burgeoning national hero, was particularly displeased by Dunphy’s behaviour. And it was not the first time the pair had clashed. Indeed, somewhat fittingly, they almost came to blows in the Englishman’s first press conference as Ireland manager.

Peter Byrne, a journalist with The Irish Times, had asked about the controversial manner in which Charlton was appointed, narrowly beating strong favourite for the job — Bob Paisley — to the position via an FAI vote.

Charlton was unimpressed by Byrne’s question and wanted him removed from the room, yet Dunphy stood up for his colleague, also provoking the-then Irish boss’ wrath in the process.

“I had thought he was a great appointment. But we had a row at his first press conference and he invited me outside. John [Giles] fixed up that and we used to go and have a drink with him where the team stayed. He wasn’t a bad man. He was very stubborn and grumpy. He just didn’t get me. We’d been friendly and then, David was banished from the team for three years, it was mad. And I just said ‘this is wrong, it’s got to stop, it’s bullying’.

“Jack thought I’d betrayed him after hanging out with him. It’s never a good idea to hang out with guys anyway. That’s what drove him mad. And then I criticised the style of football, the fact that he shamefully dropped Liam and did it very publicly in Lansdowne Road, it was shocking. Then Ronnie Whelan was next, David O’Leary… They were all good footballers. He was tough and sly sometimes. I’m not saying he was a bad man though, because he wasn’t.”

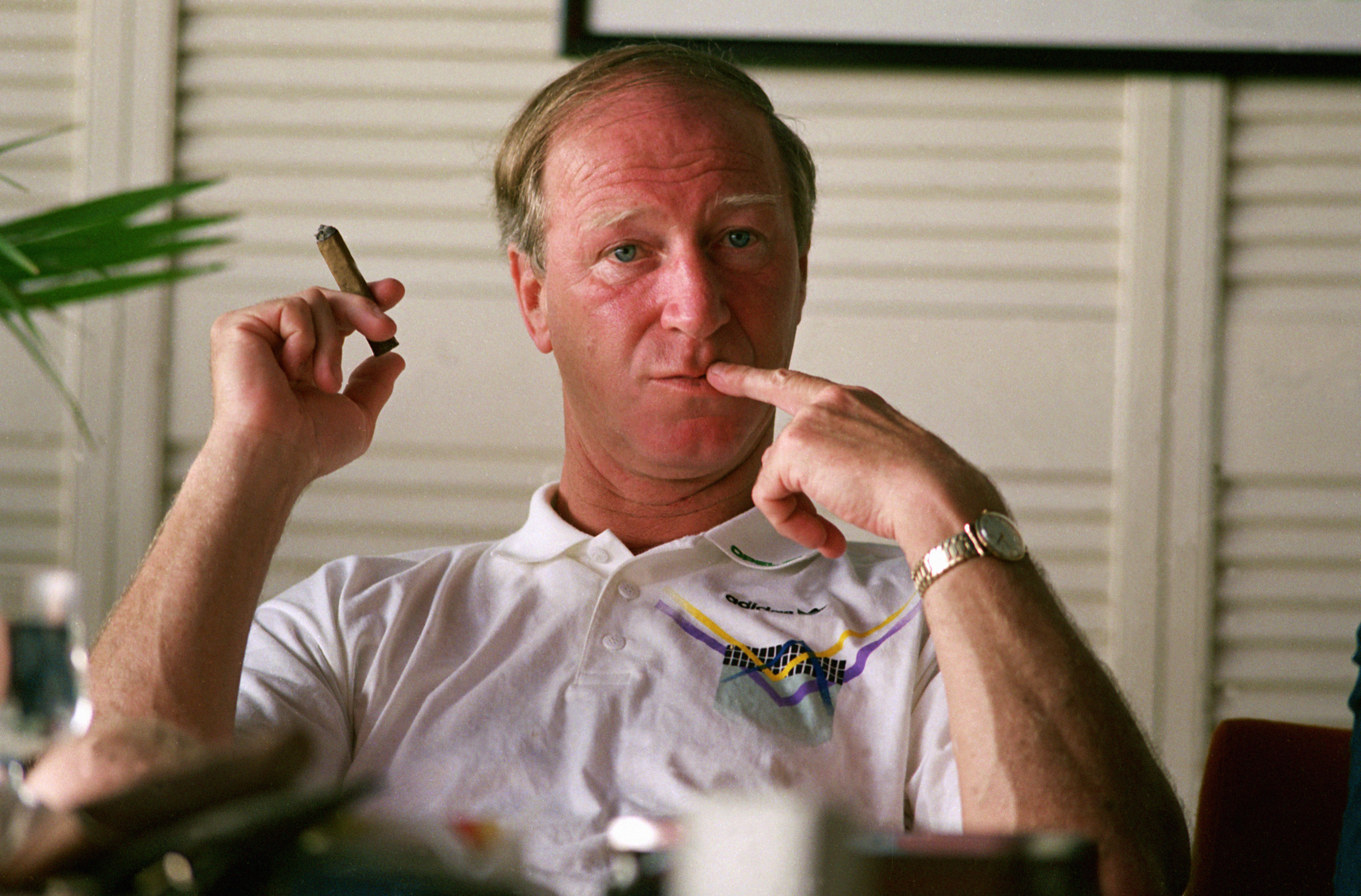

(Former Ireland manager Jack Charlton pictured relaxing with a cigar -- Claire Mackintosh/EMPICS Sport)

(Former Ireland manager Jack Charlton pictured relaxing with a cigar -- Claire Mackintosh/EMPICS Sport)

As Italia 90 drew to a close, the nation remained immersed in the euphoria of Ireland’s unexpected success, reaching the quarter-finals. Dunphy, though, had become publicly enemy number one. People raucously sang “if you hate f*cking Dunphy clap your hands” as he passed through the airport and while driving home, an angry mob briefly attempted to overturn his car while he sat helplessly inside it. My Rocky Road ends, rather tellingly, with Dunphy emotionally exhausted and seemingly overcome by the experience. As he prepares to flee to France, a waiter’s simple gesture of kindness, affording him a seat in an obscure location of a restaurant where he won’t be bothered, causes the beleaguered journalist to break down in tears.

Yet Dunphy insists that he is unaffected by most people’s perception of him.

“I think the so-called ordinary people are fine with me. They like me to say what I think. They don’t mind it. I think the media political class wouldn’t like me at all. They’d think I was trouble. They might think I was looking for attention or that I was inconsistent, which I am [laughs]. As long as my family and my neighbours are fine with me, I’m fine.

“I don’t really mind what people think. As a journalist, you can’t be worrying about that. The best you can do is work for the people that are paying you -- that means the license payer if it’s TV, or if it’s a newspaper, the readers who buy the paper. As long as they’re okay with me, that’s all I care about.

(David O'Leary celebrates scoring the winning penalty at the Italia 90 World Cup second-round match against Romania -- Ross Kinnaird/EMPICS Sport)

“I don’t want to be liked or lionised by Pat Rabbitte or Enda Kenny. In fact, I’d run very fast. It’s hard to assess. I just do my thing and hope that it works. If you’re a football fan, and you watch RTE’s football analysis, I’m there to provide a bit of fun and a bit of informed analysis. Showbiz baby! Liam and John can do the serious stuff. They’re great guys to work with, they’re a lot of fun. If we produce a good programme at the end of that, with informed and challenging analysis, then I’ve done my job. And that’s the same as a plumber might be doing his job or other journalists might be doing their job.

“I don’t have any inflated idea about it. I’m not nursing the sick, finding cures for cancer or doing anything important. It’s only journalism.”

Consequently, this somewhat relaxed attitude is perhaps what spurs the careless comments that, by Dunphy's own admission, he is occasionally prone to.

While he suggests wishing he could take comments back is “a waste of time,” he acknowledges that mistakes have been made during his time as TV’s most controversial and provocative soccer analyst.

“I have been intemperate and impulsive. During the time of the Keane thing in Saipan, I made an unkind remark about an English journalist [Rod Liddle], which was disgraceful. Saying he ‘ran away with a young one’ [laughs]. I apologised to him the following day. It was an appalling thing to say. But Bill goaded me by quoting him at me. That was an appalling thing to do. I don’t think I’ve done anything like that [since]. It shows how passionately and deeply I felt [about the Keane situation]. I lost the plot that night.

“I had good arguments with Liam about Trapattoni and stuff, but they’re real. He’s got an opinion. I have an opinion. We bash it out. But I don’t regret many things despite a few atrocities. And I said something that was probably unkind about Glenn Whelan after the last Ireland match that I slightly regret now. I said he was a terrible player… But he has got a Ferrari. The only time I saw a Ferrari was in the showroom, or on the motorway flashing past me.”

YouTube credit: Piaras Kelly

Even one of his greatest friends and closest footballing allies, John Giles, at one stage had a serious falling out with Dunphy over their different views on Roy Keane and the Saipan saga.

Yet that argument, unlike Saipan, has long been forgotten, and Dunphy never fails to speak in glowing terms about the much-heralded senior analyst nowadays.

“I’ve known of him for 60 years,” he says. “He was a legend as a schoolboy. He was a legend as a player. We played together in the Irish team. I lost a year’s wages of his, selling dodgy cup final tickets. He forgave me for it. I don’t think his wife did," he laughs.

"He’s a great guy and John earned a bad rep playing for Leeds and when he first came home to Rovers, he got terrible stick. Con Houlihan was shocking [to him], as were other media. He wasn’t very media friendly. He’s a shy, retiring sort of person. He doesn’t like the sound of his own voice. John wouldn’t be a media tart like me. So they were suspicious of him.

(Eamon Dunphy with his friend and fellow Irish soccer analyst John Giles -- INPHO/James Crombie)

“But everyone knows him now and respects him. He was the Grand Marshal for the Patrick’s Day parade for God’s sake. It’s not one of my ambitions -- I was laughing at him for doing it. He was a great player though -- good enough to play in the [present-day] Barcelona team, and so was Liam [Brady]. They could have played in any team in the world. So could Paul McGrath and Roy Keane. We’ve had some great players who were as good as any that were ever born. We’re lucky to have them on the panel, because they’re highly intelligent men as well. When they’re doing their analysis, they know what they’re doing and I think RTE are lucky to have them.”

He is equally effusive in his praise of Giles’ seven-year stint as Ireland manager.

“I think John was the best manager we ever had. Because John was manager for seven years and he overturned the shabby old regime that the blazers were running, he gave Liam [Brady], David [O'Leary] and Frank Stapleton their debuts, we started playing cultured football and John transformed it."We very narrowly failed to qualify for a major tournament and that’s what Jack did. He took us to places we’d never been. He took us to Italy. It was the worst World Cup in living memory, but still, we did it. In terms of results, he was the best we ever had. In terms of changing the culture and getting us to play the game the right way, John was a very important and influential figure.”

Giles was, of course, not the only legendary footballer who Dunphy has known intimately over the course of his life. George Best signed on for Manchester United as a teenager a year after his fellow Irishman made the switch.

The pair quickly bonded over their similar backgrounds and characteristics. Hard as it may seem to imagine given the reputations they acquired thereafter, Dunphy says their definitive characters were shyness and strong level of self-consciousness that made them feel awkward around girls. Personality traits that starkly contrasted with those of their teammate at the time -- the supremely cocky ladies’ man, Barry Fry.

(Dunphy befriended George Best while both were young players at Man United -- PA/PA Archive/Press Association Images)

“He wasn’t the George Best in the headlines then. He was just another lad," he says. "There was a gang of us. I was a year older than George. He came a year after me. So part of the thing was showing him the ropes. We went to dance halls and snooker halls -- doing all the usual stuff. And George was quiet, introspective and very, very shy. We didn’t drink then. We just had a coke.

"He had simple tastes. He used to like to go to the bowling alley, stuff like that. When he was 17, 18, he burst into international prominence by the brilliance of his play. And his world changed. He was the first superstar in soccer in Britain. And because he was such a good-looking lad, the girls went crazy for him. And George went crazy for the girls [laughs].

“It all happened very quick. George’s life was a tragedy played out very publicly. And there’s a scene late in the book where I try to get him off the booze and on to cannabis, but he’s not having any of it. He said ‘I don’t like drugs’ and I said ‘what’s that brandy you’re drinking?’ He was a tragic figure in the end, but he was a good person. His mother was an alcoholic who died early. His father was a wonderful man, Dickie, who I knew very well.”

The complex nature of Best’s character is highlighted by two memorable incidents depicted in the book. The first recalls how in the United changing room one afternoon, a young Best mockingly read aloud love letters that his teammate had written to a girlfriend -- an incident made much worse by the fact that the Northern Irishman was widely believed to be seeing this girl behind the back of the player in question. The second incident, however, took place towards the end of his life and illustrates Best’s more humane side -- detailing how he suddenly decided to play an impromptu game of snooker with a disabled kid at a talk he was giving, going out of the way to make him feel special in the process. The latter incident is one of the most heartwarming moments in the book, whereas the former occasion illustrates the United legend's renowned ruthless streak.

Thus, such inconsistency in personality, it could be argued, was yet another trait Best shared with Dunphy. Nevertheless, there was one obvious difference between the two. As Best shone at United, Dunphy flagged. Consequently, his lack of progress prompted the player to submit a transfer request, with the Red Devils eventually selling him to York City.

“My problem was that I didn’t grow," he explains. "I was very small and frail anyway. And you need upper body strength to be a really top player. And I didn’t have it. I was very light. I had the skills but I didn’t grow and smoking doesn’t help. But it’s impossible to say if I had the physique, if I hadn’t smoked...“George Best had the same physique as me but he had strength and he didn’t smoke or drink initially either. He had a kind of toughness that I didn’t have and an upper body strength, even though we looked similar. If you look at John Giles and Liam Brady, they had an upper body strength that I didn’t have. So I was never going to be a top player. I kind of saw that in retrospect.”

Great players such as Giles, Brady and Best are much rarer these days, Dunphy argues. It is a topic he has discussed on numerous occasions already and you would think, à la Alan Hansen, he would have decided by now that there was nothing left to say following a long and distinguished career in punditry. Yet the increasing fervour with which Dunphy speaks while discussing this topic tells a different story.

“No country is really producing these players. There’s a terrible dearth of talent around the world. It is in terminal decline, because the conditions in which kids play are usually poverty and the street. I’d say Messi had a humble enough background and I think Ronaldo’s background was relatively humble too. There’s a golden generation in Spain, but what’s coming after them we don’t know.

“The Germans and the Dutch keep producing players but not in the numbers they used to before. So it’s essentially a street game. And you learn it on the street and by the time you’re 10 -- say John Giles or Liam Brady or me -- someone of my relatively modest standard -- I knew everything. I had all the moves when I was 10. So then, you go to a professional club when you’re about 15 and those skills are refined. You learn to become a team player, you test yourself, so there was a process. The problem with the game now is that the process isn’t there at street level.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, the man who spent his childhood addicted to “reading and football” refuses to speak in sentimental terms about the sport he loves so ardently. On the contrary, he believes soccer will eventually die a painful death in which the money is irrevocably drained out of the game.

“It’s not imminent, but it’ll be down the line somewhere. What people are buying into now are the brands -- Manchester United, Liverpool, Chelsea, huge brands. Though the football is sometimes better in Italy, Germany or Spain, it’s the big English brands that were built by the Bill Shanklys and the Matt Busbys that endure. If you look at Tottenham, they have a few English players -- Michael Dawson, Jermain Defoe.

“But if you look at Chelsea say, there’d sometimes be no English players. And if you look at Manchester United, they only have a few. And even in Italy, which is a great footballing nation, when Mourinho won the Champions League with Inter Milan, there wasn’t one Italian player in the team, which is incredible. And Italy don’t produce the players they used to for that reason.”

Moreover, if you think Dunphy's thoughts on the future of football are bleak, it's nothing compared to his assessment of the state of modern Ireland.

"I think we have a dysfunctional political class," he says. "I think they’ve destroyed the country. Young people are deciding to leave. A lot of them are despairing. A lot of them are highly educated. And look at the hours those young nurses and doctors are working. They’ve downgraded nursing. They’ve downgraded teaching. They’re yellow-packing it. I think the country is sick. I think it’s not going to get better anytime soon.

"And the people responsible for it are walking around town, free as a bird and many of them with massive pensions. I think it’s a sickening spectacle and young people who’ve worked hard to get their qualifications and find that there is no work will leave, in fact, they are leaving in their droves. We know the numbers. And it’s a tragedy."Sometimes leaving is a choice and liberating, and in my case, it was liberating. But sometimes, it’s not. We’re training nurses, doctors and teachers and they go off and spend their lives somewhere else. But the political media class cover it up really. They don’t want to talk about it or they talk about it, but they don’t want to do anything about it. I think this is a terrible time for Ireland.

"Go back to the 40s or 50s in Ireland, we didn’t have anything, but we didn’t have hundreds of thousands of mortgage debt in our house, which a lot of people have now. There was no such thing as negative equity. I think people are afraid. People are killing themselves because of it. People are despairing because of it. Old people going around in their overcoats because they can’t leave their home. What kind of society is that in the 21st century? It’s deeply shocking."

Such grand statements attest to the flair and conviction with which Dunphy invariably speaks. Hence, as well as being a prominent soccer analyst, he has gradually developed into a genuine authority on Irish public life.

Yet for all Dunphy's passion, his bold assertions are inevitably incorrect sometimes. And on that theme, he’s already come up with the title for the second volume of his autobiography.

“It will be called ‘Wrong About Everything,’ he insists, while laughing so heartily that I’m still unsure whether he’s joking entirely. “It’s about when I fall in love with Bertie and Charlie McCreavy and Mary Harney. It’s all to come.”

YouTube credit: dbumhoedown282

The Rocky Road by Eamon Dunphy is published by Penguin Ireland. More details can be found here.