IN CONTRAST TO the ongoing chaos of their attacking intentions, France’s defence has improved with each game in this Six Nations.

While a quick glance at the table coming into this weekend shows that Philippe Saint-André’s men have conceded seven tries and a total of 78 points over the course of their four games, those figures don’t tell a complete story.

Ireland have let in just two tries and 29 points in this tournament, so clearly their defence is better than France’s? A deeper look at the statistics offers a challenge to that assertion.

Les Bleus have suffered 14 line-breaks of their defence, the same number as Ireland. They have allowed 32 offloads, four fewer than Ireland. Their number of missed tackles compares favourably with Joe Schmidt’s side too [France 66-61 Ireland].

This French squad possesses lots of powerful men. The likes of Mathieu Bastareaud, Yoann Mestri, Dimitri Swarzewski, Louis Picamoles, even scrum-half Maxime Machenaud are capable of dominating the opposition in the collisions.

That obviously applies to attack, but here we’re looking at the defensive side of the coin. Men like those listed above will come out on top of direct one-on-one contact more often than not if the opposition attack plays into their hands.

We get a strong example of that in the GIF above, with Bastareaud overpowering Luther Burrell [who is quite the specimen himself], driving him backwards in the tackle. That serves to shift the momentum into France’s favour, as well as providing a brief chance for the type of turnover situation in which they thrive [which we'll look at tomorrow].

Beyond the physical attributes of their individuals, France actually operate with a decent degree of discipline in defence. That is not in the sense that they don’t give away silly penalties [they do], but rather that they generally try to keep a very solid shape and structure.

There is nothing revolutionary in how Saint-André’s men set up when defending. The wingers will drop deep to cover kicks when the opposition is building from deep; fullback Brice Dulin attempts to hold the centre of the pitch, but then cover across to the touchline if one of his wingers is forced to join the front-line defence.

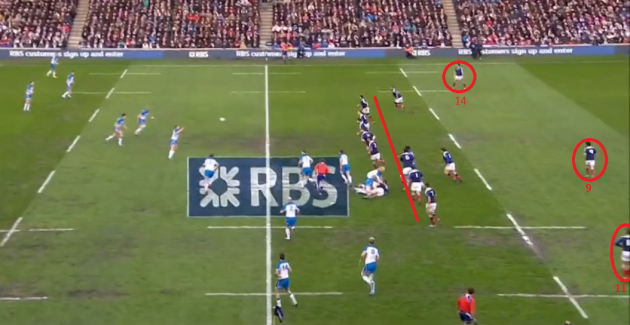

On top of that, scrum-half Machenaud will generally drop in behind the front line to cover that space in case of chip kicks or grubbers. In the photo below, you can see that shape, although Dulin is out of shot, hanging back deep to cover the long kicks.

In this instance, if Scotland move the ball through the hands out to the left, Huget will rush up to join the front-line defence, while Dulin will get across to cover the space in behind on the France’s right side of the pitch; very basic stuff.

France’s line speed is not as notably aggressive as Wales or England’s, meaning they don’t have to commit as many bodies to that front line. They are generally quite adept at drifting across the pitch in defence, using the touchline as an extra defender and covering the space effectively.

Le dix, il ne plaque pas

Clearly the French defence is not perfect though, everyone can agree on that simply from having watched les Bleus’ games so far and forming their own impressions based on what they’ve seen. There are chinks in every team’s defensive armour, and France have been no different.

Out-half Jules Plisson has been superb for Stade Français in the Top 14 this season and was handed his international opportunity when previous incumbent Rémi Talès suffered an arm injury before the England clash in round one.

Unfortunately, it just hasn’t worked out for Plisson so far with France. He had a good debut against the English, but has since regressed greatly. There are major issues with his play in attack, but here we are focused on his defensive contributions, which have been very poor.

Plisson is a relatively weak one-on-one tackler at international level. At just over 6ft and around 93kg, the 22-year-old is not the smallest man to have played for France, and he has the base level of strength to cope in the long-term.

However, his inexperience and unreadiness for the Six Nations has been partly expressed by his passive approach to defending. As demonstrated in the video above, Scotland used Plisson’s weak tackling as a means to get over the gain-line, as did Wales in their win over the French.

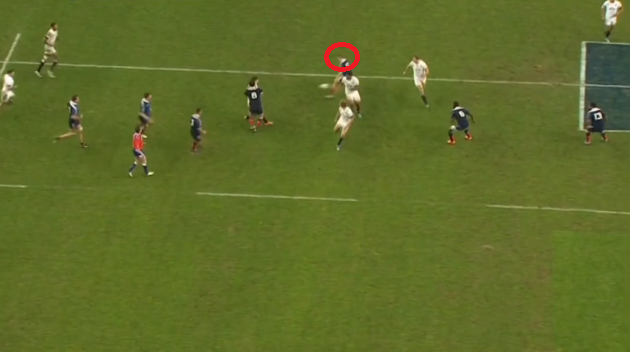

Looking to compensate for his inability to win collisions when attackers get the chance to run at him in defence, Plisson has taken to ‘shooting’ up out of the French defensive line. That is, he is sprinting up ahead of his teammates, thereby creating space either side of himself for the attack to target.

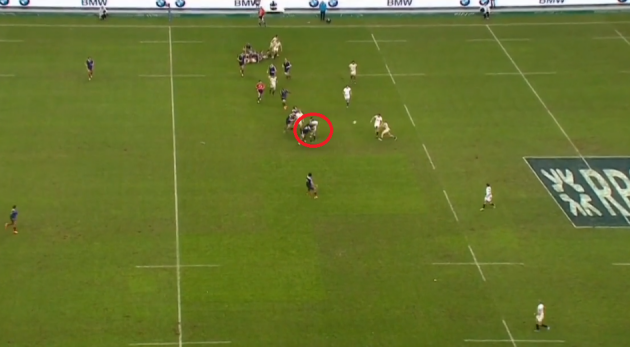

Above, we see a fine example of that, with Plisson shooting up ahead of the line in a wide channel. If Billy Twelvetrees had been more accurate in fixing his man and passing, the English would have had a decent chance of scoring in this instance.

The subconscious intention on Plisson’s part is to rush up and tackle one of the English attackers as they catch the ball, allowing him a far greater chance of dominating the collision.

What it really does, however, is turn a very defendable situation for France into a potentially dangerous one. As you can see below, Plisson [circled] has shot ahead of the rest of the line, leaving the men inside and outside him in difficult positions. Plisson is literally in no man’s land, a situation that has been repeated across all four games.

We actually examined something very similar to the above when we looked at England’s attacking play a few weeks ago. In highlighting the prototype of the English attack, with runners off the out-half busting the line and feeding another direct runner, we saw another example of Plisson’s habit of shooting out of the line.

Again, the out-half gets ahead of the men directly either side of him and compromises the French defensive line.

Plisson is looking to make a big defensive play by either hitting a ball carrier as he collects the pill, or even intercepting the pass. Both are laudable intentions, but neither is realistic in this scenario and it represents a real lack of defensive discipline from the youngster.

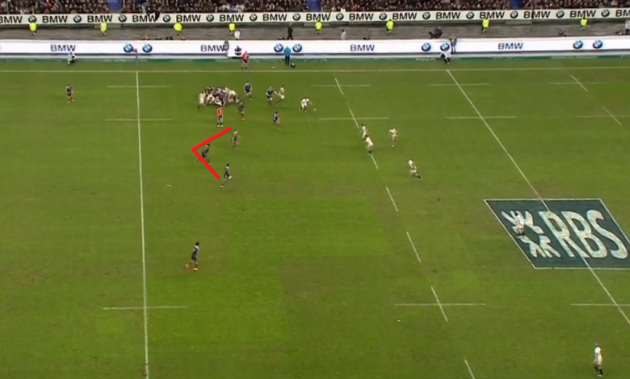

The only thing Plisson really achieves is to create that ‘dog leg’ in defence and as you can see below, the pass actually ends up being released behind his back.

A glance over the defensive statistics of the France out-half don’t make for particularly bad reading. The 22-year-old has fallen off just seven of his total 35 tackles attempts; but that is where stats so often fail us.

Those figures simply aren’t qualitative; they don’t take into account the number of times Plisson’s ‘completed tackles’ actually allowed the opposition over the gain-line to create attacking momentum, nor do they account for the times when he doesn’t even get a hand on the attacking player, like above.

Où est son pote?

Bastareaud is a rarely powerful man, as we pointed out above, but he does have some long-standing issues in defence. There is little doubt that he is a good one-on-one defender and contributes much to the French efforts [more on that below], but those moments come when the attack plays into his hands.

In terms of decision-making and agility, the Toulon centre can be found wanting in defence. With France, ‘Basta’ defends in the 12 channel very often, despite wearing the 13 shirt. That is both a recognition of his strength in close-quarters contact and his indecisiveness in the outside centre channel.

With Plisson being a relatively weak defender, one would presume that France would stack that 12 channel just outside him with as strong a defensive player as they could find, and Saint-André has turned to Bastareaud to perform that duty.

However, the Plisson-Basta defensive axis has shown real signs of frailty in the tournament so far, with the opposition attack benefiting from targeting that duo.

Above, we see a really simple example of Wales doing exactly that. It’s a straightforward ball off the back of the line-out and straight to Jamie Roberts on a hard, flat line to bust through the space in between Plisson and Bastareaud.

Ireland certainly don’t have a ball carrier of Roberts’ ilk in their backline at present, but Brian O’Driscoll has been carrying powerfully in recent times and Gordon D’Arcy is also well able to break the line. Andrew Trimble has also been used as a battering ram close into the set-piece too, so there are options there for Ireland.

What we’re looking at here is the weakness that allows Wales to break the gain line. As we can see in the shot below, Plisson has once again shot up ahead of this fellow defenders and provided that ‘dog leg’ situation for Roberts to exploit.

It’s Plisson’s error, but Bastareaud reacts sluggishly to the problem and fails to rescue the issue before Roberts bursts through. It’s worth stressing that the French out-half deserves the lion’s share of the responsibility, but the weakness is between himself and Bastareaud.

We go back to the England clash for another example that bears a strong similarity to one of those examined earlier. Again, Plisson gets up ahead of the defence [although this time it is more understandable as France are numbers down in the wide channel].

Still, had Plisson had the discipline and patience to hold his position in the line, France had enough men working across on the drift to cover the situation well. Instead, he shoots up again and presents England with another chance to exploit a disjointed defensive line.

Of note on this occasion is Bastareaud inside the France out-half. Similarly to the previous example we looked at with Roberts, the centre has been left in a compromised situation by his teammate, and again the outcome is that he fails to ‘save’ Plisson’s mistake.

Both players end up tackling the same decoy runner [Courtney Lawes], and there is a hole left in behind them. Looking at the shot below, it is easy to imagine Jonny Sexton darting into the gap now left outside the lumbering Pascal Papé.

As it transpires, England are once again fail to ruthlessly exploit the loss of defensive shape on France’s part, something we highlighted as a weakness in their game when we looked at their attack before the clash with Ireland at Twickenham.

We see another example of England possibly failing to take advantage of the weakness of Plisson and Bastareaud as a defensive duo in the video below. On first viewing, it actually appears that the English make good gains through the jinking running of Jonny May.

There certainly are positives in here for England, but again our focus is on the French deficiencies and how Ireland might take advantage of them.

Owen Farrell carries the ball to the line very effectively, and draws Plisson in before releasing his pass. The Stade Français man needs to show more ‘fight’ in this situation after he realises the pass has gone.

Just outside Plisson, Bastareaud has run into difficulties of his own as he buys the direct decoy line of Burrell. England’s outside centre runs at the inside shoulder of ‘Basta’, and the Toulon midfielder is only too happy to commit to that tackle, rather than stay on his feet as long as possible, read that pass out the back door and fight to get to May.

Basically, England manage to remove Plisson and Bastareaud from the game with a simple screen pass, leaving Wesley Fofana and Maxime Médard compromised out wide. As we see below, it’s a brief 3-on-2 in open play, even if Dulin is covering in behind on the right.

England make good gains, but there was again a brief glimmer of a chance of cutting France apart and possibly even scoring.

Add another unfamiliar figure into the mix and there’s more trouble

Defending in midfield really is a difficult task. As we saw in the most recent example above, there are difficult decisions to make about who to tackle, who to ignore and who to trust.

Building a solid defensive midfield takes communication, experience of making mistakes and mental strength, as well as sheer familiarity. Asked about his partnership with D’Arcy, O’Driscoll said the following, which could easily be extended to include Sexton:

“We just know each other’s style of play. We’ve a good ability to be able to read what one another are thinking and have a lot of comfort in being beside one another. In a lot of new centre partnerships, you need communication to be a huge aspect of your cohesion.

Whereas with us – not that there’s an element of telepathy – there’s an understanding that I don’t have with other people. I can see, having been in the situation lots of times with him, what he’s thinking”

Right now, France’s midfield doesn’t have that familiarity, even if there have been many instances of good defending throughout the tournament. The examples of poor defending come with that lack of understanding and communication.

We’ve seen above that Plisson and Bastareaud aren’t working together as effectively as might be hoped, but throwing another figure into the midfield mix with whom that pair are not totally accustomed to defending with and there is even more trouble.

In the opening rounds, Fofana was the man defending in the 13 channel very often, and one could see that there was a little lack of trust in his reading of the game based on the men inside him.

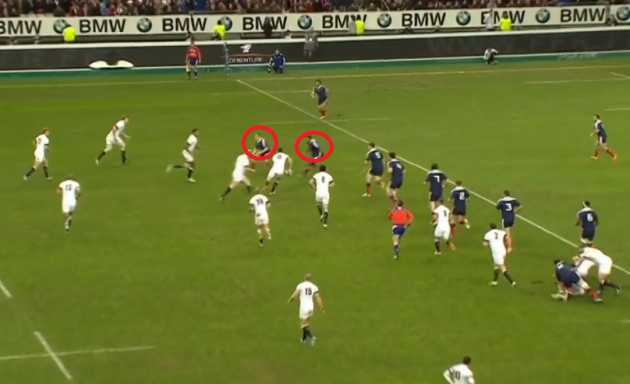

In the example above, it appears that England simply botch their midfield play [which they certainly do], but there is a defensive malfunction on France’s part in there too. Had England actually completed this mini-play [one they have attempted to use in each of their Six Nations games], France were in trouble.

The first problem is that Bastareaud gets left behind by Plisson and Fofana as they initially come up off the line in defence [below]. That immediately puts doubt into Fofana’s mind; ‘Can I trust this guy to get back up into the line? Do I need to step into his channel and make the hit?’

As it transpires, Bastareaud does in fact get up to cover the decoy-running Burrell. However, Fofana has clearly decided that his teammate isn’t going to get there, or possbily ‘Basta’ hasn’t sent such communication to the Clermont man.

As we see below, both centres commit to Burrell. The pass is sent out the back door by Twelvetrees, but the saving grace for France is that either Farrell or Jack Nowell has run the wrong attacking line and isn’t in position to accept that pass.

It’s clear that France have left themselves in an awful position by being ‘sat down’ by the decoy run of Burrell [in other words, they have been rooted to the spot by the decoy runner], and if England had completed their mini-play, there was a superb chance of scoring a try.

Fofana isn’t going to play against Ireland [he's been ruled out with a fractured rib], but the central point remains the same; no matter what way they go with selection, France will have a largely unfamiliar midfield.

Maxime Mermoz played at outside centre last weekend against Scotland and is a club mate of Bastareaud’s at Toulon. Problem solved right? Nothing is as easy as that with France; that duo have lined up together just five times this season [without great success], while last weekend was only their second outing as an international pairing.

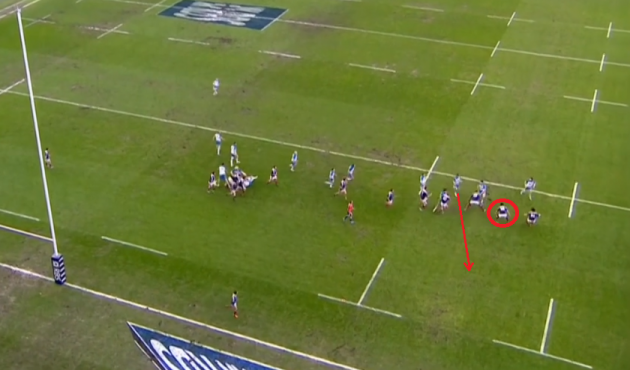

With Mermoz in the team last weekend, there remained an issue with the trio of midfield defenders, as we saw for the try scored by Tommy Seymour.

Credit goes to Scott Johnson’s men for an excellent try, but like several of the examples above, France had the bodies in place to defend this situation. There are quite a few faults to pick out in the French defence here, starting with Plisson at out-half.

The inexperienced out-half allowed himself to be taken out of the game by the decoy line of Alex Dunbar. Technically, it’s a penalty to the French for obstruction, but in reality it’s a well-run line by the Scottish centre and it happens all the time in rugby.

Again, Plisson needs to show more fight to get himself away from the decoy runner and out on to the next attacker. Outside him, Bastareaud shoots onto Matt Scott, despite the inside runner in Seymour.

A step further outside that, Mermoz and Yoann Huget are both marking the same man, when the outside centre could have been affecting the situation inside. He simply hasn’t communicated and functioned well with the men inside him.

When we freeze the frame, we can see that Mermoz [circled] is essentially doing nothing, he’s in a no man’s land of his own. Looking back on this try, he will likely feel he should have screamed as Bastareaud to ‘bite in’, or step inside onto the arriving Seymour.

That would have left France man-on-man in defence and given ‘Basta’ the type of opportunity to smash attackers in which he thrives. It’s a simple breakdown of the 10-12-13 axis for France in defence, and Ireland can look to benefit from that issue.

It seems odd that Plisson has lasted until now as France’s starting out-half, particularly as Talès is back in the squad. Saturday might be one game too far for the youngster though, and it would be no surprise to see him benched for the clash at the Stade de France.

Ireland will be hoping that is not the case, but if Talès does come into the team, there is a similar weakness in his play. The Castres man is a stronger one-on-one defender than Plisson, but he is far from eager to make big tackles.

Of more relevance is his lack of familiarity with Bastareaud and whoever gets selected in the 12 shirt. Mermoz seems likely to be retained, but the talents of Gaël Fickou are surely tempting for Saint-André too.

Whatever way that selection goes, the defensive combination will be untested and represents an area for Ireland to target.

Basta at the breakdown

Many have wondered why Bastareaud continues to be picked in France’s starting team, despite his apparent unwillingness to pass the ball and some of the defensive shortcomings we have touched upon.

That is to ignore the major contributions he makes for Saint-André’s side though, with his ball carrying a particular source of momentum for them in attack. Defensively, his breakdown work is the best in the French squad at present.

Bastareaud’s sheer bulk means that he is very difficult to shift off the ball if he is allowed to jackal immediately after a tackle, as we see below.

Questions obviously need to be asked about Geoff Cross’ rucking in the GIF above, but that’s an international tighthead prop failing to shift a centre off the ball. The issue is the split second that Scotland allow Bastareaud to get over the ball, something that happens again in the clip below.

Ireland will need to be extremely focused on ‘Basta’ in this zone immediately after the tackle. So far in this year’s Six Nations, Schmidt’s men have been the best rucking backline in the competition, with the likes of O’Driscoll, Dave Kearney and Andrew Trimble featuring strongly.

There will need to be a similarly focused effort against France to smash out the threat of Bastareaud on the deck. His 120kg+ bulk means that he is extremely difficult to shift off the ball once he gets into position, so proactive and aggressive breakdown work will be needed from Ireland.

Expecting the unexpected

In terms of selection, it’s not totally clear how Saint-André will proceed with his midfield. Bastareaud will remain in the team surely, but at out-half the claims of Talès will be hard to ignore. At outside centre, Fickou is a tempting option.

Ireland will be hoping that Plisson continues in the team for all the reasons above, and more, even if he has a creative spark that could punish them too. Talès has different habits, but he too has defensive frailties when targeted [Jimmy Gopperth showed that in the Heineken Cup this season.]

Knowing exactly what to expect from France is virtually impossible at this stage, but the overriding point is that Ireland’s midfield will be perhaps the most important attacking weapon for Schmidt at the Stade de France.

The ability to use O’Driscoll as a decoy to fix defenders, Sexton’s effectiveness on that loop play, D’Arcy’s eye for space in between the opposition out-half and inside centre; all of those facets will need to be ruthlessly used.

Trimble and the Kearney brothers can confuse and confound with animation out the back door, while also presenting real options as strike runners. The key for Ireland is that movement to unsettle a French midfield that will suffer from a lack of familiarity.

France’s defence has improved as this tournament has advanced, meaning Ireland may only get a single chance to score a try or bust the line in midfield. They will need to be at their most accurate and ruthless to exploit that opportunity in a high stakes encounter.